The abolishment of slavery and the emancipation of th slave population marked a turning point in the history of the West Indies. The British government passed the Act of Emancipationin 1833 and declared it law in the following year., freeing a slave population of around 665 000 in the British Carribbean… see more here

Roll on the future

Aapravasi Ghat

About 16 percent of the 37,000 indentured Indian immigrants who arrived between 1845 and 1917 were Muslims. Despite their small number and the adverse environment, they established Islamic institutions. The inner struggle for self-purification replaced the defensive jihad of the Maroons and the Muslim African slaves. This revitalized Islam in Jamaica. India had been ruled by Muslims from the early 13th century. The Moghuls (1526-1858) enriched India by building a great empire that still is a source of pride in modern India.

Slavery had lost its importance by the 1830s. India and China were prominent in Britain’s commerce ad trade, making enormous contributions to its industrialization and economy.

After losing the North American colonies, Britain sought to make India a classical-style colony. The British exchequer knew of the East’s immense wealth, as the East India Company’s trade in silk, muslin, cotton and piece goods had generated great wealth for Britain since the late seventeenth century.

India was the home of cloth manufacturing and the greatest and almost sole supplier of cotton goods, precious stones, drugs, and other valuable products. Evidence suggests that “all the gold and silver of the universe found a thousand and one channels for entering into India, but there was not a single outlet for the precious metals to go out of the country.”

The empire’s opulence and religious harmony gave way to violence and plunder as Britain, following its victory at the Battle of Plassey (1857), pursued a divide-and-rule policy. Evidence suggests that probably between Waterloo (1815) and Plassey a sum of £1 billion was transferred from India to British banks. Between 1833-47, another £315 million flowed into the British economy.

But Britain was not content. To meet its labour needs in the British West Indies, Britain exported about 500,000 East Indians to the Caribbean (1838-1917).

Out of 80,000 Muslims, about 6,000 came to Jamaica during the indentureship period. Their small numbers and challenges of plantation life (starvation, un-Islamic diet, deplorable living conditions in barracks shared by 25-50 adults of different origin, ages, sex, religion, kinship, and 9-hour work days) strengthened their spiritual struggle.

Many came from such predominantly Muslim cities as Lucknow, Allahabad, Ghazipur, Gorakpur, and Shahabad, all of which had witnessed the zenith of Islamic culture and social life. These Muslims ensured the preservation of Islamic identity through community solidarity, adherence to Islamic culture and values, and Islamic education.

This unity manifested itself in the establishment of 2 masjids, which institutionalized Islam in Jamaica.

Muhammad Khan, who came to Jamaica in 1915 at the age of 15, built Masjid Ar-Rahman in Spanish Town in 1957, while Westmoreland’s Masjid Hussein was built by Muhammad Golaub, who immigrated with his father at the age of 7.

This masjid was named in honor of its first imam, Tofazzal Hussein. The two masjids became the community’s spiritual centers, and united the Muslims by teaching them about Islam and its practices. They functioned like the Holy Mosque in Makkah in worship, and like the Prophet’s Mosque in Madinah in terms of the community’s spiritual, educational, social, and political life. The indentured Muslims laid the foundation of the 8 other masjids established in Jamaica since the 1960s, with the advent of an African Muslim community that now forms the largest Muslim ethnic group.

With the Indian indentured Muslims, and then with others from the Subcontinent, came the rich Moghul culture’s culinary arts, fashion, lifestyle, and aesthetic arts. Gastronomy and exotic delicacies and entertainment dishes have been appreciated at state functions, special ceremonies, and restaurants bearing such Moghul names as The Taj Mahal and Akbar.

Since the 1960s, the variety of Moghlai dishes has increased by new immigrants from the Subcontinent. These Moghul-inspired delicacies are cherished in Jamaica, and more particularly in Trinidad and Guyana.

Taken from: http://www.caribbeanmuslims.com/authors/443/Dr.-Sultana-Afroz

Tribute to an odyssey of toil – Indentured labour memorial plan awaits calcutta land JAYANTH JACOB

http://www.telegraphindia.com/1090821/jsp/frontpage/story_11390348.jsp

New Delhi, Aug. 20: The West Indies are India’s farthest diaspora, and the truth perhaps is that as a nation we are more connected to their cricket team than to the progeny from our shores.

The Indian government is now trying to make symbolic amends to pay tribute to the ancestors of V.S. Naipaul and thousands of other nameless families from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar that braved long sea voyages and slavery to give themselves and their children a shot at a better life.

It plans twin memorials — one in Calcutta, their port of embarkation, and another on Nelson Island, their port of disembarkation — to enshrine the historic, but mostly forgotten, odyssey of indentured labourers.

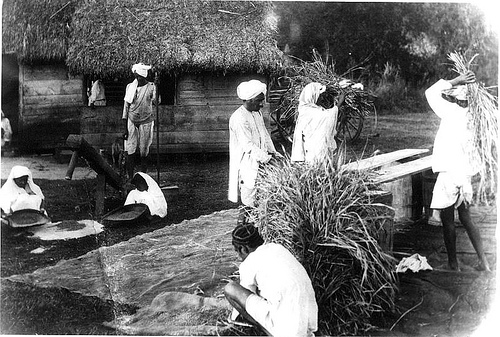

When slavery was formally abolished across the British empire in 1834, cheap labour was required to work the colonial sugarcane plantations in the West Indies. Indians, chiefly lower caste families from impoverished parts of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, were then shipped over — much like blacks before them from Africa — from the Calcutta and Madras ports.

Nelson Island was the main entry point for over 147,000 labourers who arrived from eastern India to join what was virtually a slave force on the sugarcane plantations.

The ministry of overseas Indian affairs has written to the Bengal government for acquiring land to erect a memorial near Calcutta port, from where thousands of indentured labourers, including Naipaul’s forefathers, left for Trinidad and Tobago.

The ministry is also examining a slew of proposals, including those from Indian diaspora organisations, for a memorial on Nelson Island.

“We are waiting for a response from the state government,” K. Mohandas, secretary of the ministry, told The Telegraph. “The ministry is in-principle agreement for setting up a memorial,” he added.

Sources said there were still some issues in the way like the “high price of land” around the area where the memorial is sought to be built.

“We learn that one plot which was identified had some problems as it was entangled in legal disputes. But we hope that some other plot can be made available,” a source said.

Some diaspora groups have been sending proposals to the government for consideration and a final blueprint is expected to be firmed up soon. “We are going through various proposals and suggestions,” an official said.

Fatel Razack, the ship that carried the indentured labourers, was owned by a merchant in Mumbai and was originally named Fath Al Razack, Victory of Allah the Provider. When the British decided they were going to bring Indians to Trinidad in 1845, most of the traditional British ship owners did not wish to be involved as it came after the ban on slavery.

Indian Arrival Day, celebrated on May 30 in Trinidad and Tobago, commemorates the arrival of the first Indian indentured labourers from India to Trinidad in May 1845, on Fatel Razack. The ship left Calcutta in February 1845.

But then the human cargo the Fatel Razack took to the West Indies was not merely a labour force. As history is witness, over time Indian communities became part of the cultural melting pot of the Caribbean, retaining their Indianness at the core but also merging into the cultural mosaic of those far islands.

Although the event has been celebrated among the East Indian community in Trinidad and Tobago for many years, it was not until 1994 that it was made an official public holiday there. Soon, there will be a memorial to go to on that holiday, too.